Socialist Economic Bulletin

There is a ‘magic money tree’ – it’s investment

There is a ‘magic money tree’ – it’s investmentBy Michael Burke

Supporters of austerity have long argued that there is no viable alternative because of persistent government deficits and rising debt. David Cameron put it starkly arguing that ‘there is no magic money tree’.

However these assertions contain two important fallacies. First, it is evident that, if government is increasingly indebted it must be the case that the private sector is also an increasing owner of that government debt- government cannot be a net debtor to itself. Therefore rising government debt represents a transfer of incomes, from the public sector to the private sector.

Secondly, economies can grow. Otherwise human society would still be in its most primitive phase. Therefore there is no fixed amount of output in the economy, or the monetary denominator of that output.

IMF answer

The question posed is therefore, how can a cash-strapped government grow the economy and improve its own fiscal position? The IMF has arrived at an answer. In the latest widely-read World Economic Outlook (WEO), the IMF devotes an entire chapter to the merits of public investment in infrastructure, which it defines as transport, power and other utilities and communications systems. The paper ‘Is it time for an infrastructure push? The macroeconomic effects of public investment’ can be found here (pdf).

Investment is one of the essential components of growth. Private sector investment is driven by the anticipated profit, but it has no magic wand to conjure returns from investment which the public sector does not possess It is possible for government to benefit from the returns on investment in the way that the private sector can. In fact there are additional returns on investment to the public sector that are not available to the private sector at all, in the form of increased tax revenues and lower social welfare payment from increased economic activity.

The key points of the IMF research can be summarised as follows:

- The stock of public capital, which is mainly responsible for total infrastructure, has declined across all categories of economies over the last three decades

- There is now a substantial shortfall in both the quantity and quality of public capital

- There are very high returns available to the public sector from investment in infrastructure

- In periods of low growth the immediate effect of an increase in investment in infrastructure is a return of one and half times the initial investment, which rises to three times over the medium-term

- The positive effects of investment are larger when they are financed by debt rather than by budget-neutral cuts elsewhere

- The positive effects are also larger when they are supported by monetary policy

- There is little or no evidence that the government’s cost of debt increases when debt is used to fund infrastructure investment

- In terms of what the IMF calls ‘emerging markets’ this means that the effects of investment are far higher when funded by international loans, rather than transfers from other parts of national budgets (the so-called ‘fiscal policy rule’ usually demanded under IMF country programmes).

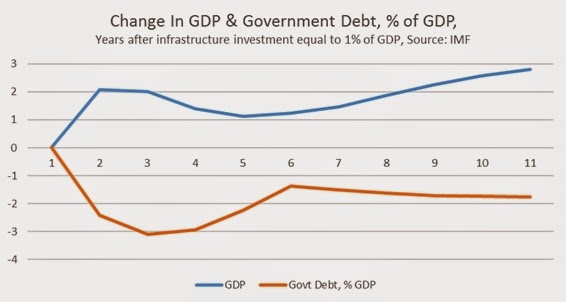

The research paper also presents a stylised version of its results for the advanced industrialised economies in the current phase of the economic crisis. The results are shown for the change in GDP and the change in government debt as a percentage of GDP arising from a 1% increase in public infrastructure investment, in Fig.1 below (data from Fig.3.9 in WEO).

The central estimate is that there would be an immediate increase in GDP and an immediate decrease in government debt arising from infrastructure investment, and that these accumulate over time. By the end of the period 2023 the research estimates that a 1 per cent of GDP increase in public infrastructure investment would raise GDP by 2.8 percent and that government debt would have decreased by 1.75 percent.

Although the IMF does not do so, the same logic could be applied to any investment which increases the productive capacity of the economy, most especially education. Public investment produces growth, which produces lower debt and deficits. Similarly, the IMF research does not explore the mechanisms by which this can be achieved. In those economies where there is a greater weight of public sector corporations, where firms and banks are under public control, they can be a direct conduit of increased state investment. The greater the weight of public corporations, the greater the government’s ability to both increase the level of investment and to regulate it.

What’s stopping them?

IMF research papers are often regarded as very authoritative, but they are not uncontroversial. Much earlier in the current crisis another WEO research chapter (‘Will it hurt?’) argued that austerity policies would be hugely damaging, depress growth and so prevent any significant improvement in government finances. This judgment has been demonstrated to be essentially correct.

Yet austerity has been implemented in most advanced industrialised countries. The effects have been so negative that for many this is the weakest recovery on record, government debt burdens have hardly lifted and now many commentators, the IMF included, are concerned about the prospects for a renewed slowdown.

Neither can there be any confidence that the most recent research will lead to a sharp increase in public investment. The key obstacle to that is hinted at in the IMF research paper. There are a number of references to the impact on private sector investment arising from an increase in public investment (‘crowding out’ effects), even though these are generally downplayed.

This might seem odd. As the authors note, across all types of economies the bulk of investment in infrastructure is made by the public sector. There is an infrastructure deficit and only the public sector can reasonably be expected to fill it. Furthermore, there is a widespread insistence that reducing the level of public debt and deficits must be the overriding or even sole objective of economic policy. As the IMF research shows public infrastructure not only increases GDP but also lowers government debt. Under these circumstances, the marginal impact on private investment levels ought to be immaterial.

However, the entire austerity policy has not delivered growth or improved government finances, exactly as the earlier IMF research warned. The governments continuing to pursue it, as in Britain, are not foolish. Austerity has another purpose. This is to restore the rate of profit for firms. If large scale public investment in infrastructure risks even a minimal reduction in private investment (as the IMF says is possible, but not likely under current circumstances) then it will be fiercely resisted by those firms and those acting on their behalf.

This explains why political parties who talk about growth and deficit-reduction are wedded to an austerity policy which delivers neither. It also explains why all the forces arguing for an end to austerity and for state-led investment should expect a long struggle ahead.

Productive investment has not increased, so there is no sustainable recovery

Productive investment has not increased, so there is no sustainable recoveryBy Michael Burke

The latest GDP data showed that the British economy is a little stronger than previously thought. The economy is now 2.6% above its previous peak in the 1st quarter of 2008 and surpassed that peak in the 3rd quarter of 2013.

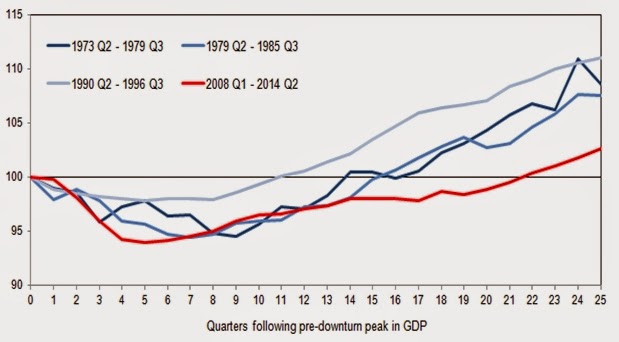

However, the fundamental character of the current crisis is unaltered by the revised data. The Office of National Statistics (ONS) is correct to state that, ‘The worst recession since our records began in 1948 has been followed by the weakest recovery’. The path of the current recovery is shown in Fig.1 below, an ONS chart which compares the level of GDP in previous recessions.

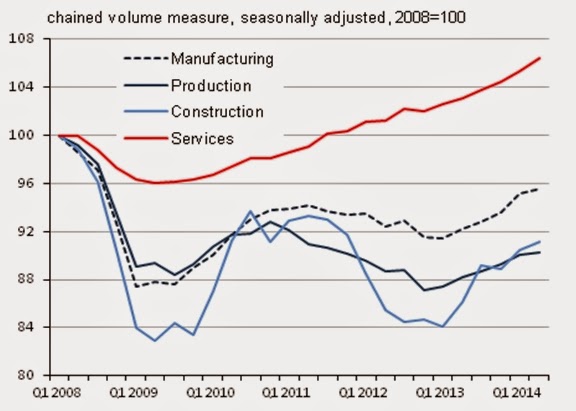

This very weak recovery is also confined to the services sector of the economy. All other sectors of the economy, manufacturing, production and construction remain in a slump. This is shown in Fig. 2 below, which records the change in the sectors of the economy from the beginning of the recession.

It is clear from this chart that there was a severe ‘double-dip recession’ caused by austerity which affected the productive sectors of the economy excluding services. A number of service industries were boosted by a combination of ultra-low interest rates and specific measures adopted by the government to boost consumption. The industries to benefit included finance, and retail and business services. Far from a ‘march of the makers’ promised by Osborne, the current situation is repeat of the errors of the Lawson Boom and the ‘candy-floss economy’, on a much weaker basis. The former Tory Chancellor argued that it was immaterial that manufacturing was collapsing under Thatcherism as long as there were overseas buyers of any good or service produced in Britain (including candy floss, in reality financial services). This was before the boom turned to bust.

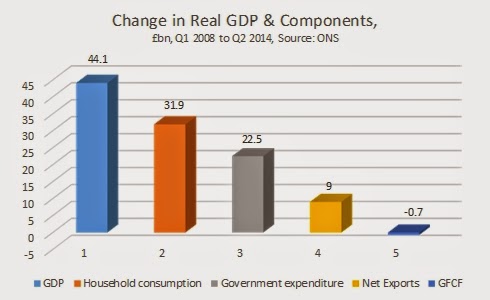

The disparity shown in the different sectors of the economy is a function of the great divergence in the components of GDP. All the main components of GDP have now surpassed their level when the recession began in 2008 except for investment. Household consumption, government expenditure and net exports are all higher, only investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation, GFCF) remains below its previous peak. The change in GDP and its components in the recession is shown in Fig. 3 below.

Key parts of the service sector can grow without significant investment, at least for a period. Industry, manufacturing and construction cannot. Investment is the main brake on the economic recovery. It is not the case that the crisis is caused by a deficiency of ‘demand’. Both household and government consumption have risen but investment is still below its previous peak. Previously, the decline in business investment was mainly responsible for the decline in GDP. But that is no longer the case.

Business investment declined far more sharply than the economy as a whole, down 23% from the peak to the low-point in 2009, compared to a 65 decline for GDP. But it has now made a feeble recovery in line with GDP.

Now it is government investment which accounts for the decline in fixed investment. Even taking into account the highly seasonal variability in government spending, the current level is 15.5% below the peak. The absolute decline (not taking account of seasonal variations) is 54%. The change in real business investment and the main component of government investment (not including investment by public corporations) is shown in Fig. 4 below.

This illustrates a central plank of the austerity policy. The decline in business investment proceeded the recession, driven by a declining rate of profit. (This point ought to be wholly uncontroversial as even the mass of profits fell in nominal terms at the beginning of 2006). After the fall in profits in 2006 the level of investment in the productive sectors of the economy began to decline and then fell rapidly producing the recession. For the period which includes most of 2006 and 2007 this decline was masked by the last stages of a housing and financial bubble. The level of real investment in the productive sectors is shown in Fig.5 below.

This important decline in the productive capacity of the economy is masked by the statistical practise of referring to Gross Fixed Capital Formation in its entirety, which includes both productive investment and other large items such as residential investment and the transaction costs of investment in buildings, including estate agents, surveyors and the like. While these may be necessary and can provide a social good, they do not increase the productive capacity of the economy.

None of the productive sectors has yet seen a recovery in the level of investment from their peak level. Investment in offices and factories is the largest component and is 16.4% below its previous peak, a fall of £23.1bn.

There is therefore no ‘puzzle’ at all to the crisis of productivity in the British economy. The productive capacity of the economy is not growing and may even be declining once capital consumption and real depreciation are taken into account. If more labour is deployed, which is the case currently, output can increase. But if the productive capital of the economy is stagnating or even contracting, then this can only be reducing average output per hour. This is the underlying cause of the crisis of living standards and of real pay. Workers are working longer in less productive ways and so are being paid less.

The austerity policy includes a deep cut in government investment with the false assertion that the private sector will fill the gap. Evidently this has not occurred. The fact is that the fall in government investment is now the largest single impediment to recovery. Given the interrelationship between government and the private sector, this will have a depressing effect on private sector investment. The reverse is also true. A large increase in government investment would lead the whole economy to a sustainable recovery.

Is Ireland experiencing a boom?

Is Ireland experiencing a boom?By Michael Burke

The economy in the Republic of Ireland expanded by 1.5% in the 2nd quarter and by 6.5% from the same period in 2013. This leaves the economy well below its previous level but is actually much stronger than the annual growth rates in the same period in Britain’s ‘boom’, of 0.9% and 3.2%.

For a number of decades the Irish economy has grown more rapidly than the British economy and per capita GDP is higher in the Irish Republic. According to the OECD this is true if constant prices and Purchasing Power Parities are used, or whether current levels are used for both.

This relative outperformance is likely to continue in the future. This is because the Irish economy is more thoroughly integrated into the world economy (or, put in classic terms, it has a higher participation in the international division of labour). This is true even taking into account the effect of multi-national corporations booking profits in Ireland based on production that takes place elsewhere.

The British economy too has its own mechanisms for facilitating international tax avoidance, including the network of overseas territories Guernsey, Jersey, Gibraltar, BVI and so on.

Once this ‘soufflé effect’ is removed it is clear that the export of goods from Ireland is a vastly greater proportion of GDP than are British exports. This, combined with the tendency for an increase in the international division of labour, which is expressed as the faster growth of world trade than domestic GDP, means that the Irish economy is set to grow faster than Britain over the longer term.

But faster growth than Britain is a poor yard-stick. It is utterly foolish of British supporters of austerity to gloat over the relatively better performance of the British economy than the French economy. Declining prosperity elsewhere does not constitute economic well-being here.

Similarly, the focus should be on what is the maximum sustainable growth rate for the Irish economy and the mechanisms to achieve that. In light of the Irish economy’s degree of integration into the world economy, the current rebound in Irish GDP falls well short of what is possible or desirable.

A version of the article below first appeared on Irish Left Review under the title Investment Remains the Key to a Real Recovery.

===============================================================

The Irish recession which began in the final quarter of 2007 is the most severe in the history of the state. GDP contracted by 12.1% in a little over two years ending in the 4th quarter of 2009. That slump is not over. The latest data for second quarter of 2014 show that the economy still remains 3.4% below its pre-recession peak. In effect it is likely to take 5 years or more simply to recover the output that was lost in in the slump.

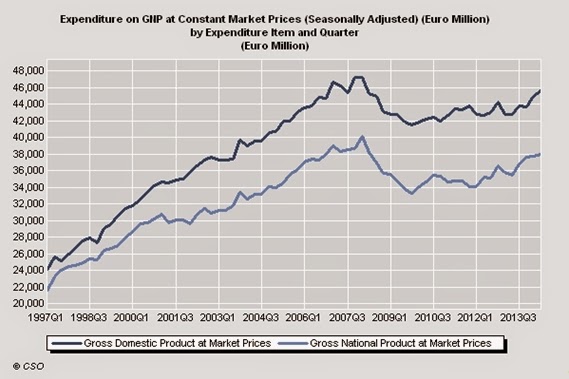

Even then, the economy will remain way below its previous trend rate of growth. This is illustrated in Fig 1 below, which shows real GDP and real GNP from 1997 to the present. The average annual growth rate of the Irish economy from 1997 to 2007 was approximately 6%. Maintaining the trend rate of growth would have led the economy to be approximately 50% larger than it is currently, and there is a danger that this potential is lost permanently.

The causes of the slump are very clear. Over the entire period of the crisis the fall in investment more than accounts for the entirety of the decline in aggregate measures of output, either GDP or GNP. GDP in the 2nd quarter of 2014 is still €6.6bn below its late 2007 peak. Investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation, GFCF) is €14.4bn below its peak. There are other components of GDP which have also failed to recover, notably personal consumption and government expenditure. But even taken together, their combined fall of €10.1bn is less than the fall in investment. The only component of GDP which has risen is net exports. The change in components of GDP is shown in Fig.2 below.

This data belies the notion that there is an ‘export-led recovery’ under way. Recorded net exports have grown very strongly, up €30.5bn over the period. But only one quarter of this or €7.4bn is a rise in the export of goods. A much larger statistical contribution has arisen from the decline in the imports of goods, down €14.6bn. As both investment and consumption have fallen, this simply suggests that both firms and households have been priced out of world markets by reduced purchasing power. The remainder of the rise in net exports is derived from international trade in services. These are particularly prone to the tax-induced flow of funds that plague the Irish economy and completely distort the economic data. There is little benefit from attempting to unravel them.

More importantly, it is clear that exports have not led a broad-based recovery at all. All the main domestic indicators of activity, consumption, government spending and investment are still far below their pre-recession peaks.

The recovery

The low-point for the Irish economy was reached in the 4th quarter of 2009. There is not yet a recovery. But there is a rebound from that low-point, which has not always made smooth progress. Every year since 2009 has seen at least one quarter of economic contraction. It is hoped that 2014 will be different.

One reason for this volatility in the data is the activity of multinational corporations. For example one large order for aircraft, none of which are produced in Ireland but are booked in this jurisdiction, can provide a large one-off boost to GFCF and to GDP.

The engine of the recovery is also clear if we take the inflection point from the 4th quarter of 2009 to the most recent data. This is shown in Fig.3 below.

The rebound in both GDP and GNP since the end-2009 low-point is driven solely by the rise in net exports. Of the €24bn rise in net exports over that period just €8bn is a rise in the net export of goods.

Otherwise there has been no improvement in the other components of GDP even during this phase. Personal consumption and government expenditures have fall by a combined €2bn. Again, this is exceed by the fall in investment, down €2.7bn since the end of 2009.

The motor force of the Irish economic slump has been the fall in fixed investment. Ireland’s openness to the world economy (its high degree of participation in the international division of labour) provides a real benefit to the economy, even if that is vastly overstated in the official data.

But for exports to lead the economy investment must grow. Otherwise Irish goods (and genuine services) become priced out of world markets. The investment strike in Ireland has not ended. Until it does there can be no confidence in the sustainability of any eventual recovery.

Austerity is on course to be a lot worse

Austerity is on course to be a lot worseBy Michael Burke

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has produced its latest assessment of the economic crisis and its impact on government finances (pdf here). In common with the UK Treasury the OBR tends to underestimate the impact of austerity policies and consequently has a persistently over-optimistic outlook for the British economy. This is no surprise as the OBR uses the Treasury economic model.

Even so the detailed analysis by the OBR is very valuable as it reflects official thinking on the economy and on economic policy. This view will continue to be shared by the OBR and Treasury beyond the next election.

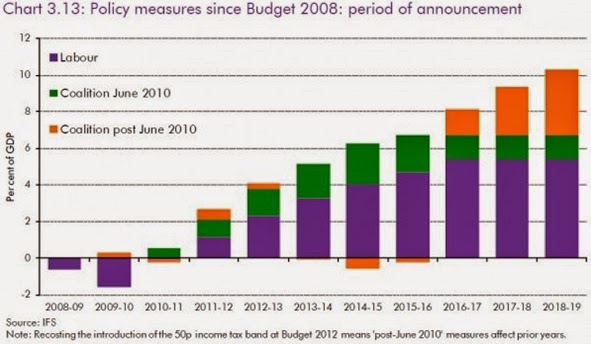

A key conclusion of the latest report is the assessment that austerity policies are set to continue for some time to come. The chart below shows the OBR’s assessment of the austerity policies and their composition from 2008/09 with projections until 2018/19. The policy measures of government spending cuts and tax change changes are expressed as a percentage of GDP.

The OBR persists in projecting the effects of Labour policy over the entire period even though the Coalition has been in office since May 2010. Labour’s austerity measures (announced by Alistair Darling in March 2010) are shown in purple. The additional measures introduced by the Coalition in June 2010 are shown in green. The further measures after that time (beginning with the Austumn Statement in 2010 and March 2011 Budget) are shown in orange.

Currently we are approximately midway through the Financial Year 2014/2015, when the fiscal tightening rises from 5.1% of GDP to 5.6% of GDP. So the current fiscal tightening is approxumately 5.35% of GDP. By 2018/19 the OBR projects the entire austerity policy will reach 10.3% per annum.

In effect we are currently only half way through the austerity programme.

At the TUC, Geoff Tily points out that that the entire OBR analysis is based on an incorrect framework (adopted from the Treasury). This framework assumes that austerity reduces the deficit while doing little damage to the economy. Yet the OBR’s own data show this assumption is incorrect.

The data below is extracted from the OBR’s Chart 1.3 in its latest report. It shows the level of Total Managed Expenditure versus Current Receipts as a proportion of GDP during the entire period of the crisis to date.

Since FY 2008/09 expenditure has fallen by just 0.6% while receipts have also fallen by 0.2% of GDP. The OBR forecasts that this will improve imminently, but forecasts of that type have been made ever since the OBR was established. The latest data for the current Financial Year actually show the deficit widening once more. The effect of austerity policies is to produce the weakest recovery on record while the reduction in the deficit has been minuscule. If 5% or more fiscal tightening has been required to reduce the deficit by just 0.4%, the OBR projections of further policy measures shown in Fig. 1 are likely to be a significant underestimate.

A continuation of austerity policies is unlikely to produce a different outcome. Unless there is a radical break with OBR/Treasury thinking, austerity is set to get a lot worse.

Austerity killed off improving productivity. Investment is needed to revive it

Austerity killed off improving productivity. Investment is needed to revive itBy Michael Burke

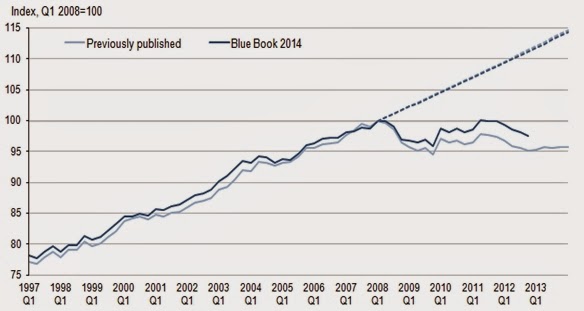

Supporters of government austerity measures have been quick to claim that recent revisions to GDP growth show a much shallower recession and much stronger recovery than previously thought. These claims are factually incorrect. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) accurately summarised the effect of its revisions as follows,

“Although the downturn in 2008-2009 was shallower than previously estimated and subsequent growth stronger, the broad picture of the economy is unaltered. It remains the case that the UK experienced the deepest recession since ONS records began in 1948 and the subsequent recovery has also been the slowest.”

The current situation for the British economy is characterised by an exceptionally weak recovery. The actual increase in output is minimal, much worse than any previous recovery. The very slow improvement in GDP is a product of more people working longer hours for less pay.

In the most recent reassessment of the data, the ONS noted the continuing exceptional crisis of productivity (the amount produced per hour of work). This is shown in Fig.1 below. The dotted line shows the previous trend growth in productivity. The unbroken light blue line shows the previous ONS data and the dark blue line shows the most recent revision.

It should be noted that productivity had been growing very moderately from the end of 2009 until the Coalition’s austerity policies began to take effect at the beginning of 2011. There has been no recovery since.

This is far worse than any previous recovery, as shown in Fig.2 . It is unprecedented in Britain for productivity to be lower than the pre-recession peak 6 years previously. But that is what the previous estimate (unbroken black line) shows. The more recent revision (broken black line) is slightly better but is unlikely to alter the main trend.

In the average of previous recessions and recoveries, productivity was 16.3% higher 6 years after the recession began. The complete data for the current slump is yet to be published. But if it is still below the pre-recession level (as seems likely) then the gap between the current trend in produtivity and the recovery from previous recessions could be in the order of 17% or 18%. There is also no sign of improvement.

If output per hour does not increase it is exceptionally difficult for average pay to increase. That would require a sharp rise in labour’s share of output, which is extremely rare when output is not expanding. This is the cause of the wage crisis in the British economy.

In a market economy there are also great difficulties in raising social expenditure when there is no growth in productivity. In any event is impossible to both raise wages and increase spending in education, health, transport, housing and so on if there is no increase in output per hour.

The cause of the productivity crisis is no puzzle. Just as a heavy load can be lifted much more quickly by machinery than by hand, productivity increases with the amount and sophistication of the capital machinery that is used. Cutting back on that equipment, by refusing to invest and/or letting existing machinery dilapidate will reduce output per hour. This is what has happened in Britain and many other western economies.

The argument that all that is required is increased demand is false. The final up-to-date data for the British economy will certainly show that demand, both household and government consumption have recovered since the recession. But investment has not. Increasing consumption by reducing investment is the road to impoverishment.

Private firms do not exist to satisfy demand, but to accumulate profits. Currently they remain uncertain about profits, and there is growing opposition to increased private investment.

But government has no such constraints. It can invest because the investment is necessary and reap returns not available to the private sector in the form of increased tax revenues and lower social security payments. State-led investment is needed before the crisis can be ended.

Austerity is the cause of the crisis in France. Investment can end it

Austerity is the cause of the crisis in France. Investment can end itBy Michael Burke

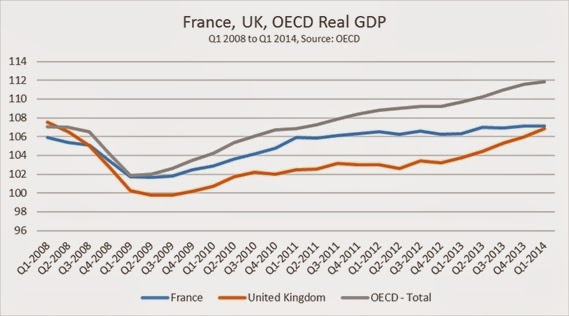

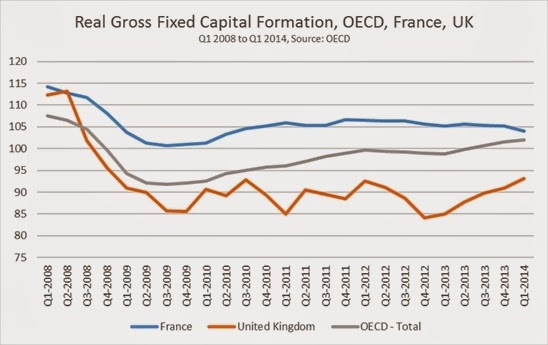

The French economy is in a grave crisis, much worse even than the sluggish growth of the OECD countries and almost as bad as Britain. In the 6 years since the beginning of the crisis the OECD economy as a whole has grown by just 4.5%. Over the same period the French economy has grown by just 1.2%. This is closer to the British economy, which was still 0.6% lower than when the recession began. The data is shown in Fig. 1 below.

Supporters of the Tory government’s austerity policy have bizarrely attempted to congratulate themselves on the recovery in Britain as the following quarter finally saw the British economy exceed is previous peak. But 0.2% growth in over 6 years is the worst performance since the Great Depression.

Similarly, there is an absurd attempt to portray the situation positively in Britain because it is better than the crisis in France. This is both factually incorrect (in the 2nd quarter of 2014 the French economy was 1.2% above its pre-recession peak) and meaningless. However bad the sitation in France, this would make no-one in Britain better off.

Investment Strike

In reality, the cause of the crisis in France has the same source as the crisis in the OECD as a whole and in the British economy. It is the fall in productive investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation) which accounts for both the severity of the initial recession and the prolonged character of the following stagnation.

The various trajectories of each economy have also been determined primarily by the chages in investment (GFCF). Initially the crisis in France was much less severe than the in the OECD as a whole because the fall in investment was less sharp. By contrast, investment fell further in Britain and the recession was sharper than in either France or the OECD. However, the recovery in French investment stalled in mid-2012 almost immediately after Hollande won the Presidential eelction and began to apply austerity policies.

By contrast, OECD investment has been painfully slow to recover. But it has been on an upward trend since the 3rd quarter of 2009, which accounts for the steady crawl out of recession. In Britain the ludicrous zig-zags of government austerity policy killed off a weak recovery in 2010. But large government subsidies to reflate a housing bubble have had the effect of increasing consumption and house building from its all-time low from the end of 2012. These trends are show in Fig. 2 below.

The French Crisis

There are two key indicators of the role of the slump in investment as the cause of economic crisis in France. These are the performance of investment relative to other components of the national accounts and investment relative to its previous trend.

Investment in France began falling once more when the Hollande government began implementing austerity policies. Prior to that point, the right-wing Sarkozy administration had talked about the need for austerity, but was generally keeping these measures in reserve in the hope of getting re-elected (similar to the Tory government from mid-2012 onwards, with a similar lack of success likely).

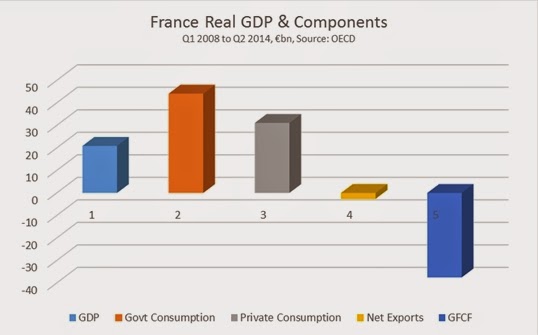

Fig.3 below shows the real performance of France’s GDP and its components from the beginning of the crisis to the 2nd quarter of 2014. In aggregate GDP is almost €21bn higher than it was in the 1st quarter of 2008. Investment (GFCF) is the only component of GDP which remains significantly below its pre-crisis level. Consumption by both the private sector and of government is higher. The problem of the French economy is not primarily a crisis of ‘aggregate demand’. It is investment, not consumption which is the brake on a genuine recovery.

Private consumption is over €31bn higher and government consumption is strongest of all at over €44bn higher. This also belies the idea that austerity is aimed at reducing government spending. Pro-business parties are far less concerned about increasing government spending if this is directed towards consumption. They are opposed to an increase in government investment, which interferes with the dominant role of the private sector in the ownership of the means of production. Despite much talk about the ‘bloated state sector’ in France government investment is actually a smaller proportion of the total than in the Anglo-Saxon countries of the US and UK (just 15.3% of the total in the most recent 2011 data).

Investment is now €37.5bn lower than its pre-crisis peak. It has fallen from 20.4% of GDP to 18.2%. Only net exports are also negative, but the decline is much less significant with a fall of just €2.6bn. The performance of real GDP and its components is shown below.

The trend decline in investment is equally stark. Investment has fallen by 9.9% in a little over 6 years since the crisis began. In the comparable period prior to the crisis investment had expanded by 18.9%. If this prior trend growth rate of investment had been maintained, it would now be €109bn higher. This would directly add 6% to GDP even before any productivity effects from higher investment are taken into account. GDP and the investment trend are shown in the Fig. 4 below.

The resources for investment

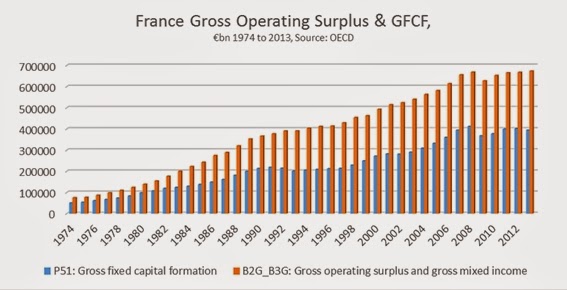

If there were no idle resources in the economy it would be necessary to constrain consumption in order to finance investment. But that is not the case currently. In common with most OECD economies (including Britain) the profits of French firms have been recovering.

In nominal terms the profit level (Gross Operating Surplus) peaked at €668bn in 2008. But after a slump in 2009 profits have turned slowly higher and finally recovered (in nominal terms, not taking account of inflation) to €674bn in 2013. But investment has continued to fall and is now €17bn lower than in 2008. The investment ratio (investment as a proportion of profits) has therefore declined.

This is the culmination of a long-term trend. Fig.5 below shows the nominal level of profits and the investment for the French economy over the last 40 years. At the beginning of the period the investment ratio was approximately two-thirds. In 2013 investment was €395bn compared to profits of €674bn, an investment ratio of just 58.6%. Simply restoring the former investment ratio would increase the level of investment by approximately €40bn. Instead, the level of uninvested profits continues to grow.

France is not in crisis because of the Euro. The main features of the crisis are the same as in Britain, which maintains its own currency. Nor is it true that the crisis of the French economy is caused by a bloated state sector. On the contrary, government investment as a proportion of total investment is now lower in France than in either the US or UK.

This is actually a key part of the problem. The crisis is accounted for by the fall in investment. The private sector is on an investment strike. This is exacerbated by the cuts in the government’s own level of investment.

The resources exist to resolve the crisis throught state-led investment. This can be funded by using uninvested profits of the private sector. A certain proportion of this can be done indirectly via government borrowing, especially as borrowing costs for 10 years are just 1.25%. It can also be done directly, directing the state-owned enterprises and the the commercial banks to increase investment, as well as other measures.

Three charts to explain why most people are getting poorer

Three charts to explain why most people are getting poorerBy Michael Burke

Most people in Britain are getting poorer. For obvious reasons, the government and supporters of austerity would prefer not to discuss this fact.

Yet in the strained language of the Labour right, there has also been a clamour for Ed Miliband to ‘change the narrative’ on the economy by no longer talking about the cost of living crisis. This is based on the completely false notion that that the economic recovery under way will inevitably produce higher living standards. This fails to understand the content and purpose of current economic policy. It is also based on a refusal to face facts.

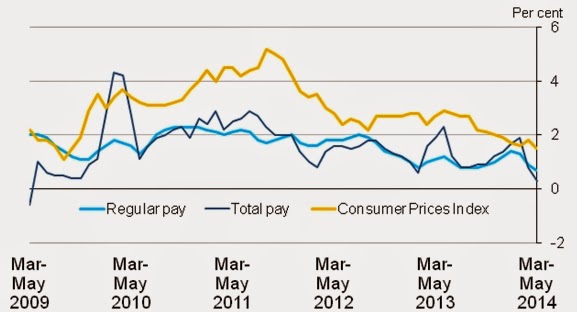

Some of the key facts on the cost of living crisis are glaringly obvious. The chart below shows the change in regular average pay as well as the change in total pay including bonuses. Also included is the change in consumer price inflation.

Under four years of the Tory-led Coalition, regular pay has fallen by 5.25%. This real decline in pay is understated in two ways. The first is that the CPI is a narrow measure of prices. In particular it excludes housing costs. Broader measures of inflation have tended to be higher over the last four years. In addition, only the pay of employees is captured by these average wage data. Anyone forced to work in self-employment, casual or other work without a regualr wage is not included in the data. These categories, along with part-time workers, have formed the bulk of the jobs growth over the last period, which has been a key factor in depressing wages generally. A broader, more accuarate picture of average wages would show a picture that is much worse.

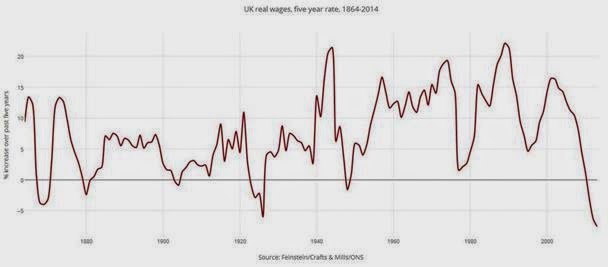

It also seems as if the fall in living standards on this measure is unprecedented. The chart below is via Ed Conway, economics editor of Sky TV, who regularly provides very useful economic data. It shows the cumulative fall in real wages over a 5-year period.

This shows real wages contracting by 7.6% over that time period. Real wages have not fallen so sharply since records began in 1864, not even in the Great Depression of the 1930s. As we have already seen, there is also no end in sight. Wages continue to fall behind inflation.

This is the key fact which underpins the ongoing cost of living crisis. But it is not confined to the issue of wages. Of a total British population of 64 million on latest estimates, only 30.6 million are in work. The rest, the majority of the population, are mainly comprised of young people, the elderly, the unemployed and economically inactive. They too have tended to experience a fall in living standards as social security entitlements and public services have been cut. They are often at the sharpest end of the cost of living crisis.

Austerity At Work

An obvious question arises, if the economy is recovering in real terms how is it that real wages have fallen so sharply? The answer is twofold. First, the population is growing, so that GDP per capita remains significantly below its 2008 level, before the recession.

But the content of austerity is to transfer incomes from labour and the poor (such as wages, or the benefits of social security as well as public spending) to capital and the rich (in the form of profits, tax breaks, tax cuts, privatisations, and so on). The aim is not to lead to stagnation, which is a consequence of the investment strike by firms. The aim of austerity policy is to boost the returns to capital. Under conditions of stagnation, this can only be achieved by reducing wages and the transfer payments to workers and the poor.

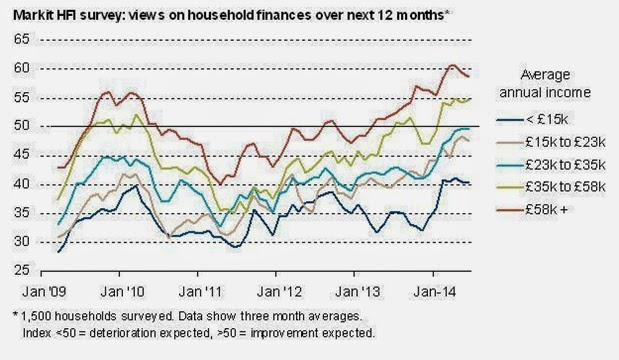

This can be seen directly even in the form of incomes and prosperity. The chart below is via Chris Williamson, chief economic at economic survey and analysis firm Markit. It shows expectations of household finances over the next 12 months by income bracket. In effect, the higher income households tend to be more optimistic on average about their living standards, while the poorer are more pessimistic. The poor are getting poorer. Among the rich, the lion’s share of the recovery is claimed by the ultra-wealthy, the owners of capital, landlords and so on.

The Tory Party sees no reason to change these trends of the economic policy that led to them. They would carry out more of the same, renewing the austerity offensive that has been soft-pedalled ever since the poll ratings plummeted in 2012.

Labour is currently debating economic policy. Evidently, it would be wholly counterproductive to abandon the focus on the cost of living crisis now, which is already the deepest on record and is continuing. Yet the scale of this crisis also means that any policy is appropriate to the magnitude of the crisis. SEB has previously outlined some of the measures that could be taken. All proposals and policies need to be assessed in light of the extremely grave economic crisis that Labour will inherit in 2015.

Hoarding cash while refusing to invest

Hoarding cash while refusing to investBy Michael Burke

The world’s largest companies are hoarding cash and cutting productive investment at the same time. The Financial Times reports a survey from one leading ratings’ agency, Standard & Poor’s, which shows that the 2,000 largest private firms globally are sitting on a cash mountain of $4.5 trillion, which is approximately double the size of Britain’s annual GDP.

Yet capital expenditure, or ‘capex’ by those firms fell by 1% in 2013 and is projected to fall by 0.5% this year. But this does not presage an upturn. Steeper declines in productive investment are projected by those firms in both 2015 and 2016. Taken together, if these projections materialise the actual and projected falls in capex over the 4 years from 2013 to 2016 will approach the calamitous fall in productive investment seen at the depth of the recession in 2009. This is shown in the FT’s chart below.

SEB has previously argued that companies are not prevented from investing by lack of access to capital or similar factors. They are sitting on a cash mountain. The same is true of British firms. There is plenty of money left, but firms refuse to invest it.

This is because private firms are not concerned with growth, either GDP growth or the growth of their own productive capacity. They are primarily driven by the growth of their own profits, or preserving them. Where that is not possible, where new capex will not meet an expected level of return, no new investments will be made.

The survey findings are reinforced by recent research from investment bank Morgan Stanly, which focused on the US economy. It argued that there were two reasons to expect little improvement in productive investment. One is that the US economy is far below using all the existing manufacturing capacity currently available, so has little need to add new fixed capital. The second reason is that shareholders tend to oppose heavy commitments to new, large-scale investment. Managements that do not invest are rewarded by shareholders, while those that do are punished (lower share ratings, lower financial rewards for managers and ultimately, loss of job if the investment turns sour).

Contrary to mainstream economics, this indicates that the interests of shareholders are not ultimately aligned with those of society as a whole. Instead the interests of shareholders frequently stand opposed to an increase in productive investment, which is the key mechanism for raising productivity and living standards.

Or, as another investment bank shows, the greater the long-run returns to shareholders, the lower the growth rate of GDP, and vice versa. The chart below is from CSFB and has previously been used by SEB. It shows the relationship between average shareholder returns and average GDP growth over a number of countries from 1900 to 2013. GDP growth is strongest where the returns to shareholders are lowest, and vice versa.

This has clear and direct implications for economic policy. The Tory-led government has attempted to encourage private sector investment with a series of inducements, bribes, subsidies, privatisations and so on. But it has not worked.

In the latest GDP data for the 1st quarter of 2014, business investment in the British economy remains £25bn below its previous peak level in the 1st quarter of 2008, even though GDP as a whole is £10bn below its previous peak. Total investment, which includes the government and the household sectors is now £49bn below its previous peak. The fall in investment accounts for the stagnation of the British economy and the main investment deficit originates in the business sector. The trend in business investment is shown in the chart below.

A continuation of the same policy is unlikely to yield different results. Instead a radical, reforming Labour government could direct investment itself, using the available resources. Even the current government has recently ‘fined’ Network Rail for to failing to meet its targets and will use the proceeds to upgrade wifi on the rail network, that is to engage in productive investment on a very small scale.

The same logic on a vastly greater scale could be applied to the problems of declining energy capacity and the need to de-carbonise the economy. Fines running into billions could be legally applied to the privatised energy companies if they fail to meet new legislative targets on investment in renewables and energy efficiency. The proceeds can then be used for direct state investment.

These and other methods could be applied to a series of key sectors, banking, energy, transport, health, education, infrastructure and so on. If the private companies still refuse to invest, government can use the fines to invest directly itself. In fact there are any number of methods of achieving the same objective. But, as the surveys and analysis from the financial sector show, the private sector currently has no intention of leading an investment recovery as profits have not yet recovered. So the state must lead an investment recovery.

The levers government can use for investment

The levers government can use for investmentBy Michael Burke

At a certain point in the next few months the recession in Britain will officially be over as the real level of GDP will finally exceed its previous peak in the 1st quarter of 2008. The media coverage will be generally very favourable, in the hope that this will boost the Tory vote and vindicate the austerity policy. In reality it will do neither. The economy was already recovering modestly when the Coalition took office and the austerity policy reversed that upturn. This is the weakest and most drawn out recovery since the 19th century.

Nor is the hoped-for political impact likely to materialise. One reason why the Tory vote in opinion polls has hit a ceiling fractionally above 30 per cent is precisely because of austerity. The policy is designed to transfer incomes from labour and the poor to capital and the rich. At the same time, the austerity policy of cutting state investment undermines any robust or sustainable recovery. The economy overall continues to stagnate and only a fraction of society feels any benefit from the recovery. During this ‘recovery’ most people’s living standards continue to decline. The political impact is that the Tory Party can shore up its core vote, but not add to it.

It is important to be clear about the task that will face an incoming Labour government. Labour will inherit a crisis, not a recovery. While the economy will soon recover its pre-2008 level, this represents 6 years of lost output. Living standards should have been rising, but they have not because of economic stagnation. Instead, living standards for the overwhelming majority have fallen as a direct result of austerity policies. A continuation of austerity policies after 2015 would produce the same result of economic stagnation and falling living standards for the majority.

Chart 1 below shows the medium-term trend growth for the British economy, and its current performance. The economy is approximately 16% below its previous trend level of growth. There is no evidence to suggest that this gap between previous and actual growth rates will close in the foreseeable future.

This means the poverty created during the slump will become a semi-permanent feature of the British economy. An incoming Labour government would need a radically different policy in order to achieve a very different outcome. It would need to address the cause of the crisis.

The fall in investment remains the main brake on recovery, led by the decline in private sector investment. On current estimates, GDP in the 1st quarter of 2014 was still £10bn below its peak level in the 1st quarter of 2008, but investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation, GFCF) remains £50bn below its level at the same time. The slump in investment more than accounts for the current stagnation. The private sector has been unwilling to lead investment higher, so government policy must lead the way.

How to pay for investment?

Since Britain was not a high-investment economy even before the current crisis, £50bn a year in additional investment over the lifetime of the next Parliament is the minimum that would be required to resume trend growth. Replacing lost output and investment would require a further £320bn to avoid the loss incurred in the recession becoming permanent.

These are enormous sums, approaching the level of the bank bailout in 2009. There is no appetite for borrowing on this scale, even though there is clearly a case for some increased government borrowing to fund productive investment, especially when government interest rates remain close to zero in real terms.

Therefore, the bulk of the funds must come from another source. If it were really the case that ‘there is no money left’ then that would be the end of the matter. But it has already been noted that sometime in the near future the economy will recover its pre-crisis peak. Logically, this means there will soon be more money, more resources available than was the case before the recession, not less.

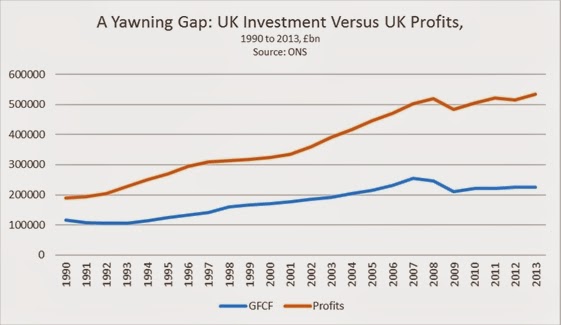

There is money left, it is simply not being invested. There is a yawning gap which has emerged between the level of investment (GFCF) and the level of profits. In 1990 the level of uninvested profits was £73bn. In 2013 it was £307bn. Even if we take profits after the effects of taxes and subsidies, the level of uninvested profits has risen from £5bn to £97bn in 2013. This is because taxes on production have been cut repeatedly over the period. The trend in uninvested profits is shown in Chart 2 below.

What levers for a radical, reforming government?

Since the fall in investment accounts for the continued stagnation of the economy and corporate profits are not being invested at an increasing rate, it follows that any serious discussion on reversing the slump must be focused on the mechanisms for directing those profits towards productive investment.

The key areas for that investment remain home building, infrastrucure, energy, transport and education.

In passing, it should be noted that the uninvested profits themselves have number of different destinations, all of them with negative consequences. The main destinations for uninvested profits include increased executive pay and returns to shareholders in the form of dividend payments and share buybacks, which have all reached record levels. In addition, there is a growing cash mountain held in the bank accounts of British non-financial companies. It remains unused by them (and most is held in accounts yielding little or no interest). But it is used by the banks partly to fund increased speculation in financial assets, including housing, international stock markets and commodities, including foodstuffs.

Levers for investment

I . Using the banks One unintended consequence of the financial crash of 2008 to 2009 was to increase the role of the state in the economy, even, or especially in countries where governments were committed to laissez fare policies. In Britain a very large section of the banking industry remains in public ownership in the form of RBS and Lloyds banks, through the body UKFI. At the same time all banks operating here are subect to licensing, authorisation, regulation and capital requirements from the Bank of England and other public bodies.

Prior to deregulation and Thatcherism, the Bank of England used to engage in ‘credit direction’. This was largely done informally, but in some detail so that banks would be instructed not only as to the amount of credit they should provide to the economy, but to which sectors and in which proportions[i]. The formal powers and associated bodies now are far greater and renewed credit direction actually runs with the grain of current regulation, which favours lending to governments as far safer than lending to corporations.[ii]

The government has a wide array of measures it can use to instruct the banks to provide credit for productive investment. The government could create special vehicles in order to channel that credit, or use existing ones (see below). Where bank executives prove reluctant to follow those instructions, the summary dismissals of Fred Goodwin from RBS and Bob Diamond from Barclays demonstrate the public sector’s power over the banks, if it chooses to exercise it.

II . Transforming existing schemes In the post-World War II period all economic recoveries have been led by government spending. In that sense, this recovery is no exception. The crucial difference is the content of that government intervention, which has increased current spending, but slashed public investment. It has supplemented this with a series of subsidies for investment to the private sector.

These schemes include, funding for lending, help to buy, guaranteed profits for the builders of nuclear power stations and innumerable other schemes. One part of the nuclear guarantee alone may cost government £17.6bn[iii].

Without incurring any additional costs, a reforming government could simply reverse the priorities highlighted by these policies. For example, it could transform the Help to Buy Scheme which boosts house prices but not home building. Instead, it could offer the same £40bn in government guarantees to local authorities to build homes, at no extra cost but from which there would be an additional public sector revenue in the form both of income taxes from newly-employed builders and rental income from public sector tenants, as well as building desperately needed new homes.

The same logic applies to the whole panoply of government schemes. So, the nuclear subsidy should be scrapped and the same subsidy provided to generate renewable energy in which the state has a controlling revenue share.

III. Cutting waste All cash-strapped governments project huge savings from cutting waste which often remain unrealised. This is frequently because the biggest, most wasteful areas of expenditure are sacrosanct and not to be touched.

In Britain one of the biggest areas of wasteful spending is on the Private Finance Initiative and the generalised outsourcing of contracting and supplies by the public sector. Even George Osborne began as a critic of PFI waste and promised to replace it. Instead, in grasping how dependent private sector profits are on this subsidy from taxpayers, the Coalition has maintained PFI and expanded it. In the current and next Financial Year the level of private sector capital spending under the PFI amounts to just £3.3bn, which is only a portion of the total capital cost. Yet the private sector will be receiving £20bn in ongoing current payments over the same two-year period[iv].

This is a colossal waste, amounting to a direct subsidy to the private sector that the public sector could and has done more cheaply. New PFI could be ended, all existing contracts scrutinised for their potential to be rescinded and a new enforcement body established to apply the highest possible service conditions, again with the threat of cancelling contracts.

IV . Cutting Trident and defence spending £100bn could be saved by a decision not to renew the Trident missile system[v]. Clearly, nuclear weapons of mass destruction cannot possibly provide any economic benefit. Trident is not even an independent system, so could only be used under US authorisation and then in all likelihood only as part of a global nuclear conflagration which would have Britain as a prime target.

The notion of Britain ‘punching above its weight’ received an historic reversal with the decision not to bomb Syria. Yet British defence spending remains way above European countries, which have perfectly adequate defence. Cutting British defence spending to their average would release nearly £20bn for alternative purposes.

V. Taxation Government priorities were clear when increasing VAT but cutting corporate taxes, costing the same amount. This was a direct transfer from the poor to capital. Similarly, cutting the 50p tax rate while imposing austerity on the majority was a clear example of the logic of austerity.

Less widely remarked, the government also removed tax incentives for genuine investment while cutting the corporate tax rate. The effect was a higher rate of tax for those that do invest, and a lower one for those who do not, including the banks. All of this was done in the name of stimulating investment, which has not materialised. This is because private investment is driven by the rate of profit. Keeping a larger post-tax share of dwindling profits will not drive up private investment.

These priorities could be reversed at no cost, and no loss of investment. The tax system could be used to improve living standards and boost genuine productive investment while at the same time penalising those firms who refuse to invest but have high dividends, executive pay or share buybacks. Higher taxes on unearned income, speculation and capital gains could be combined with tax breaks for investment and lower taxes on the poor.

VI. Removing private sector subsidies A large number of private sector firms receive government subsidies for running monopoly services that can, and have been performed more efficiently in the public sector. These include, but is not confined to areas such as the railways, utilities such as water, energy, and even NHS procurement and provision.

A consequence of privatising natural monopolies is that the private firms maximise revenues simply by raising prices and cutting costs by reducing the quality of the service. At the same time, successive governments have created a system where public funds are used to subsidise the private sector firms. Removing these subsidies (guaranteed income, inflation-plus price rises, direct grants, and so on) would save both government and service users enormous sums.

The most well-known example is the privatised rail franchises, where the process of renationalising the franchises could be accelerated by a stricter insistence on the terms of the franchise contracts in terms of service, investment, fares, and so on. But a creeping privatisation has been under way for the NHS under successive governments. In 2011/12 the private sector obtained £8.7bn from the NHS for providing services, £8.3bn in secondary care[vi] and £2.8bn in drugs and other procurement for a total of just under £20bn. Detailed data is difficult to obtain, but the level of the private sector take of NHS spending will have risen dramatically under this government[vii].

VII. Renationalisation There are clear benefits in renationalising the privatised companies in terms of the government’s ability to direct investment. Higher levels of investment in turn lead to better services, lower costs and increased or better paid jobs for the workforce.

But there is also a fiscal and strategic economic benefit to renationalisation that meets the objection that a cash-strapped government must have other priorities for its limited resources. The real position is that renationalisation increases government resources and allows them to be directed to boost the economy.

This can be illustrated with the example of Royal Mail. Royal Mail pays a dividend to its private shareholders from the profits it generates and the dividend yield is 3.8% (for every £100 shares owned, the shareholder receives £3.80 each year). This will rise each year if the company grows. But the borrowing cost to the British government when it issues new debt to be repaid in 10 years’ time is currently 2.7%. Buying the entire shares of Royal Mail (renationalisation) would cost the government less in interest than it would be able to receive in dividends from the company itself. It would generate additional resources, which could be used to reduce the deficit, or better still, to increase investment on which there is an even greater return.

The same logic applies to the privatised energy and utility companies, whose dividend yields are all even greater than Royal Mail’s. There is also a strategic imperative. The energy companies have been creaming off profits since they were privatised, and not invested in either additional energy capacity or in renewables and carbon-reduction. Spare energy network capacity was approximately 25% when they were privatised and different estimates now put it at between 4% and 8%. In response to Ed Miliband’s promise of a temporary price freeze, they threatened an all-out investment strike, that they would ‘turn the lights out’. This may happen anyway in the near future, given the decline in network capacity.

This is not a situation any government should allow. Ed Miliband has committed the next Labour government to decarbonising the economy by 2030. Given the resistance of the energy companies to even a modest price freeze, and their complete unwillingness to invest on the scale necessary to meet energy requirements, renationalisation is the only realistic option. Given the huge dividend payments currently made to private shareholders (5.2% for Centrica, 5.3% for SSE) there would be a very large benefit to government finances from their renationalisation.

VIII. Living standards The focus on living standards is the correct one, and led to Labour rising sharply in the polls. Given that living standards for the majority continue to decline, it remains the right theme to focus on.

The simplest way to restore living standards for those in work is to raise the national minimum wage to the level of the living wage, and to strictly enforce it. While boosting the living standards of millions of people, the single biggest beneficiary would be government itself, since the bulk of those in receipt of social security and other government payments are in work, not unemployed. This highlights a general truth, that the interests of a radical reforming government are aligned with those of workers and the poor.

The main objection is that firms find paying the living wage unaffordable. But we have already noted the huge level of uninvested profits, executive pay and returns to shareholders. These can be cut to make it affordable. Where there are genuine cases of small, shoestring firms operating at the margin, there could be some transitional arrangements to help preserve employment. But these would only be temporary measures, and would still oblige all firms to pay the living wage. Otherwise, the effect is to allow inefficient and super-exploitative firms to compete with efficient firms that pay decent wages, embedding the ‘race to the bottom’ in the economy.

IX . Equality A similarly robust policy should be adopted in pursuit of genuine equality. The most scandalous treatment of women has been a hallmark of the austerity drive, with the pay gap widening, reduced employment, greater burdens of childcare and other household burdens, reduced public services, and so on.

Without any cost to government it could strictly enforce equal pay provisions for all firms. Again, government itself would be the largest single beneficiary of this. There is too a recognition that investing in universal childcare provides a wider economic benefit, which naturally has a positive fiscal impact. But a similar approach should also apply to the issues of all social care and reduced public services, where the burden of removing them has fallen mainly on women. The public sector is more efficient provider of these services. If the economy is being boosted by a large-scale investment programme, preventing women from taking their equal place in the workforce on equal terms is a brake on the optimal development of the whole of society and the economy.

A similar approach should inform policies in relation to the equality of black people and ethnic minorities in the economy and wider society. Black youth are living in a different country to their contemporaries, suffering Greek-style levels of unemployment. Combatting unequal pay, and inequality in terms of access to jobs, housing and education need to be central to an economic programme that attempts to utilise all the talents of its citizens. In that light, the perpetual campaign against immigration is wholly counter-productive. The strong growth produced by an investment-based recovery will both attract and require additional immigration to Britain. The alternative is to create a slum which attracts no-one.

The discriminations based on sexual orientation and on disability need to be confronted. Basic human rights are being denied causing untold misery and the whole of society and the economy is poorer as a result.

Conclusion

The 9 points above are not designed to address every possible aspect of the economic and social crisis that will confront a Labour government, and are far from an exhaustive prescription. Instead, they are designed to highlight some of the key steps a radical, reforming government could take to address the scale of the economic crisis that will confront it.

Individually, none of the measures is very radical. All governments used to engage in ‘credit direction’ before the 1970s, windfall taxes were imposed by John Major and the postal system was nationalised by Gladstone. They only seem very radical because the political spectrum has shifted so far in the direction of those who caused the current crisis.

Taken together, these measures would allow the state to lead an investment-based recovery using the main levers that are currently available to it in Britain. That would be a major reform of the British economy and of society. A more enduring transformation would require other levers and a different alignment of social forces to be pulling on them.

[i] See the paper from Victoria Chick and Sheila Dow, Financial Institutions and the State: A Re-examination (pdf) http://www.postkeynesian.net/downloads/soas12/VC080612.pdf

[ii] Under the Basel III capital adequacy rule for banks, their lending to governments has a zero risk-weighting while lending to companies has a risk weighting (requiring additional capital to be set aside) of 50% (pdf), KPMG, Basel III: Issues and implications, http://www.kpmg.com/Global/en/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublications/Documents/basell-III-issues-implications.pdf This is one of the many reasons banks are generally campaigning against the Basel III regulatory regime.

[iii] FT, UK nuclear deal with EDF could waste £17.6bn, says Brussels http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/ac6a7924-8a68-11e3-9c29-00144feab7de.html#axzz35Z5HVgFD

[iv] UK Treasury, Private Finance Initiative Projects 2013: Summary data (pdf) https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/267590/PU1587_final.pdf

[v] CND, People not Trident (pdf) http://www.cnduk.org/images/stories/briefings/trident/People_Not_Trident_report_CND_Mar14.pdf

[vi] Nuffield Trust: Public and private provision (pdf) http://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/files/nuffield/publication/130522_public-payment-and-private-provision.pdf

[vii] FT, Private groups invited to help NHS buy services, February 25, 2014 http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/bcf1269c-9e1a-11e3-95fe-00144feab7de.html

Recent Comments